Education

Summer Research Uncovers Toxic History of 19th-Century Books

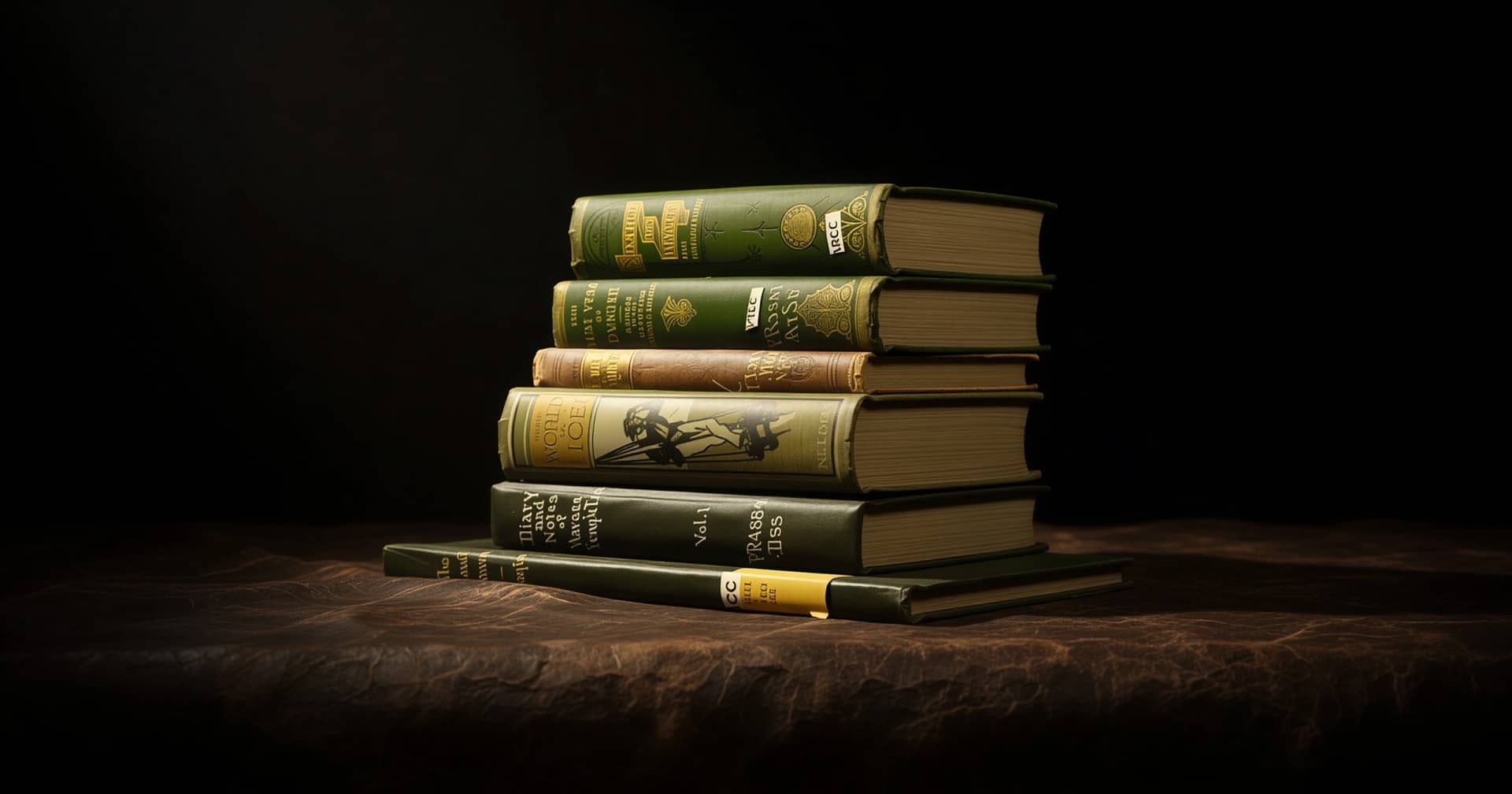

A summer research project at Western University has revealed the hidden dangers of 19th-century books, prompting a closer examination of what are known as “poison books.” Karen Wen, a third-year English major, embarked on this investigative journey after a class with Professor Kyle Gervais led her to discover the use of potentially toxic materials in historical texts.

Initially, Wen’s family was alarmed by her summer plans, questioning why she would engage with items that could contain poison. Their concerns were understandable, especially when Wen herself reacted with shock upon learning that some manuscripts might be laced with dangerous pigments. A vibrant white pigment in one medieval manuscript raised alarms about lead content, but it was the discussion led by special collections librarian Deborah Meert-Williston that piqued her interest further.

Meert-Williston explained that the bright green bindings of certain books from the Victorian era, made with a copper-arsenic compound, were particularly notorious. These books, often referred to as poison books, were popular for their aesthetic appeal, despite the hidden risks they posed.

Wen’s fascination grew as she learned about the Winterthur Poison Book Project, an initiative at the University of Delaware, founded in 2019. This project focuses on identifying and safely handling collections that may contain toxic materials, particularly from the 19th century. With guidance from M.J. Kidnie, a professor in English and writing studies, and mentorship from Meert-Williston, Wen began a rigorous examination of Western’s library collections.

Over several months, Wen scrutinized more than 7,000 books, utilizing the Poison Book Project as a reference to identify potentially dangerous titles. Her analysis not only aimed to catalogue these materials but also explored the social impact of such books, highlighting the tension between preservation and accessibility within library systems.

Through this research, Wen identified 96 books that contained potentially hazardous pigments. She emphasized the importance of understanding the cultural context surrounding arsenic usage, which was often seen in a different light during the 19th century, when it was commonly used in products ranging from cosmetics to medicines. “Today, when people hear the word ‘poison,’ they immediately think of lethal danger,” she noted. “But arsenic was also used in beauty treatments, showing how its meaning has evolved over time.”

Wen’s search involved a meticulous matching process with the Winterthur database, where she visually scanned library shelves for books with green bindings. One notable title, The Paragreens on a Visit to the Paris Universal Exhibition by Giovanni Ruffini and John Leech, underwent testing in Western’s Earth and Planetary Materials Analysis (EPMA) Laboratory. Results confirmed the presence of both copper and arsenic in the book, validating the need for her research.

While Wen’s findings thus far are significant, she believes that many more potentially toxic volumes remain unexamined. “It’s a bit of a double-edged sword,” she remarked. “From a public safety perspective, it’s good that fewer books might be harmful, but from a historical standpoint, there’s so much to learn from these texts.”

Experts involved in the Winterthur Poison Book Project assert that as long as the pigments are not ingested, the books do not pose a significant threat to the public. Still, they have developed safety protocols for those who handle these books. Meert-Williston explained, “We put them in bags with labels informing users that the bindings may contain arsenic and recommend washing hands after use.”

Wen’s research has highlighted the complexities surrounding the preservation of literary history. Many books may have been rebound over the years, and when they are physically altered or destroyed, the historical context tied to their original materials is lost. “We lose the embedded stories of how these books were produced, circulated, and understood,” she said.

Through her work, Wen encourages a more nuanced understanding of what constitutes a “poison book.” She believes in critically assessing the context of these materials rather than fostering a blanket distrust. “Just because it’s poisonous doesn’t mean that it’s evil,” she concluded.

As Wen’s internship comes to an end, she reflects on her experience with a newfound appreciation for the layers of history contained within books. “To not judge a book by its cover,” she said, capturing the essence of her research journey. This summer, Wen’s exploration into the hidden dangers of literary history has not only illuminated the past but also enriched her academic perspective.

-

Science3 months ago

Science3 months agoToyoake City Proposes Daily Two-Hour Smartphone Use Limit

-

Top Stories3 months ago

Top Stories3 months agoPedestrian Fatally Injured in Esquimalt Collision on August 14

-

Health3 months ago

Health3 months agoB.C. Review Reveals Urgent Need for Rare-Disease Drug Reforms

-

Technology3 months ago

Technology3 months agoDark Adventure Game “Bye Sweet Carole” Set for October Release

-

World3 months ago

World3 months agoJimmy Lai’s Defense Challenges Charges Under National Security Law

-

Lifestyle3 months ago

Lifestyle3 months agoVictoria’s Pop-Up Shop Shines Light on B.C.’s Wolf Cull

-

Technology3 months ago

Technology3 months agoKonami Revives Iconic Metal Gear Solid Delta Ahead of Release

-

Technology3 months ago

Technology3 months agoApple Expands Self-Service Repair Program to Canada

-

Technology3 months ago

Technology3 months agoSnapmaker U1 Color 3D Printer Redefines Speed and Sustainability

-

Technology3 months ago

Technology3 months agoAION Folding Knife: Redefining EDC Design with Premium Materials

-

Business3 months ago

Business3 months agoGordon Murray Automotive Unveils S1 LM and Le Mans GTR at Monterey

-

Technology3 months ago

Technology3 months agoSolve Today’s Wordle Challenge: Hints and Answer for August 19